|

|

|||

|

Traditionally accepted as being Saxon for "(Place of) Readda's People", the name may be Celtic Rhydd-Inge or "Ford by the Water Meadows" which fits the town's topography rather well. The river would, of course, be the Kennet, not the Thames. Tradition says St. Birinus founded a small chapel on the site of St. Mary's church in the 7th century. In 979, Queen Aelfthrith transformed it into a royal nunnery, in repentance for murdering her step-son, St. Edward, King & Martyr. It was later destroyed by the Danes in 1016, but, with four of her nuns, the Queen appears on Reading's Coat of Arms. At some time St. Mary's became a Saxon Minster, hence nearby Minster Street. The top of this lane was once called Tothill, indicating a Saxon lookout point. Another interesting street-name is the Butts where the townsfolk would have practiced their archery (especially after an act of Edward IV enforcing them to do so on Holy Days). The town had a minor Saxon mint during Edward the Confessor's reign, when Corff and Brihtric the Moneyers lived there. Royal Reading mints re-emerged in the reigns of King Stephen, Henry II, Richard I, King John & Edward III. Reading Abbey was founded by King Henry I in 1121 as a private mausoleum for his family. It was built on the site of the Danish stronghold set up during the Viking Wars of King Alfred's reign (871). They used it as their countrywide invasion headquarters, and the King besieged them there several times. At the time of the Civil War between Henry's daughter, the Empress Matilda and her cousin, King Stephen, the Abbey was still being built. The latter apparently constructed a motte and bailey castle in its grounds, possibly to harass Wallingford, though this was a little distant. It was destroyed by the Empress' son (later Henry II) in 1153 but its exact site is unknown. The mound that can still be seen in the Forbury Gardens is not the old motte, part part of the Civil War defences of the town. The Abbey was finally completed in 1164, forty-three years later. It was consecrated by the Archbishop of Canterbury, (Saint-to-be) Thomas Becket.

The following were married at Reading Abbey:

The following are buried at Reading Abbey:

Reading was where the oldest recorded British song, Sumer is icumen in, was written, but its major claim to fame was as one of the great pilgrimage centres of medieval England. It had been given the Hand of St. James by King Henry I (found blocked up in the ruins two hundred years ago and now in Marlow Roman Catholic Church (Bucks)) & the Head of St. Philip by King John. It also held some 232 other relics. The Tudor monarchs were frequent visitors to Reading. There is an old story that King Henry VIII once locked up the Abbot of Reading in the Tower of London so he could win a bet made with him while in disguise. This is commemorated by a pair of ghosts who appear in the area. They are supposedly the King taking the Abbot to London. There are two horsemen, both stout huntsmen in Lincoln Green. One beckons on a cloaked companion. The horses' hooves make no sound. At the Dissolution, despite their being good friends, the King had the Abbot hanged outside the Abbey Gate. The Abbey's Inner Gateway is one of the few remnants of this once great house still standing today. It was the original home of the forerunner of the 'Abbey School' (now in Kendrick Road) and was attended by Jane Austen. There are some ruins of the Abbey's chapter house and associated features in the Forbury Gardens, where the largest lion in the World stands as a memorial to the Royal Berkshire Regiment killed at the Battle of Maiwand in the Afgan Wars. It was sculpted by local artist, George Blackall Simonds, in 1886. The other substantially intact Abbey building that remains today is the dormitory of the pilgrims' hospitium or guesthouse of St. John the Baptist. This stands beside the path through St. Laurence's churchyard. The rest of the complex lies beneath the town hall (designed by Alfred Waterhouse and Thomas Lainson). It later became the abode of the Royal Grammar School of Henry VII (now Reading School), Stables for Henry VIII's horses when the Abbot's House became his palace for a short time, the Barracks of Civil War Soldiers and, in 1892, the home of University College Reading (now the University of Reading: hence St. James' scallops on its arms). Nearby can also be seen: window tracery removed from the St. Laurence's Parish Church after WW2 bomb-damage, a wooden memorial to a man killed in a whirlwind and the stone of a lost memorial brass ejected from the church when the money for its upkeep ran out! St. Laurence's was built by the Abbey monks for the worship of the people of Eastern Reading. Its north chancel housed the hospitium's Chapel of St. John, connected to the guesthouse by a private door and wooden cloister. The demolished south aisle was originally the Knollys Chantry and up till last century housed many of the family's hatchments. Sir Francis Knollys and his successors lived at Abbey House and, later, Caversham Park. Reading's Protestant Martyr, Jocelyn Palmer was tutor to his children. Sir Francis' grandaughter, Letitia, married one of the Vachells from Coley Park. They had a town-house known as Finch's Buildings (in Hosier Street, pulled down in the 60s), from the roof of which she is said to have watched a Civil War skirmish at Caversham. St. Laurence's has several ancient brasses, one a palimpsest. Numerous others have (like that in the churchyard) long since disappeared, notably that of the wealthy clothier, Henry Kelsall (1494), whose brass included a representation of the Jesus Bell which he had donated to the church the year prior to his death. There is also a striking 17th century wall monument to John Blagrave. He was a well-known mathematician in his day, and Lord of the Manor of Southcote. Note the allegorical ladies around him: they represent various three-dimensional shapes. Blagrave's Piazza (1520) once adjoined the church's south side. It housed the borough stocks and ducking stool, and had a small lock-up at one end. This was the site of the Abbey's Compter Gate that adjoined the church and served as a prison both before and after the dissolution. The borough pillory was nearby in the centre of the market-place. Now mostly covered over, the Abbey's millstream, the Holy Brook, once ran open through the streets of Reading. It is a natural brook which splits from the Kennet at Theale, only to rejoin it just behind the Reading Central Library (which stands on the site of the Abbey Stables) in King's Road. It is behind this building that the Holy Brook emerges al fresco to be spanned by the original arch of the Abbey Mill. You can find glimpses of it elsewhere in the town though, notably beneath one of the town's newest shopping arcades. The Grey Friars of St. Francis of Assisi arrived in Reading in 1233, hoping to administer to the town's poor. The Abbot did not want a rival religious order in Reading but, being under Royal patronage, he was obliged to give them a small parcel of land. This was on the edge of town, on the way to Caversham Bridge. The land was too marshy though, and the friars complained to the Archbishop who, being a greyfriar himself, quickly intervened. The friars were relocated in what later became known as Friar Street. After the Dissolution, their church was granted to the town as a Guild Hall. Their previous home, at the end of what became Yield Hall Lane, was small and rather noisy - due to the cries of the washerwomen on the banks of the Kennet outside! The building survived until the mid-nineteenth century. The new hall at Greyfriars was also found to be unsuitable and the Corporation moved out after only twenty years. It then became a hospital/workhouse/prison, before falling into disrepair. It was eventually rebuilt and reconsecrated as a church in 1863. The Corporation, meantime, had moved to the old refectory of St. John's Hospitium, which is why the town hall later developed on the land adjoining it to the west.

The Archbishop of Canterbury (1633+), William Laud, was born at 47 Broad Street, where Boots Pharmacy now stands, in 1573. His father was one of Reading's many clothiers and he sent him to Reading School. The great Francis Walsingham, Secretary of State to Queen Elizabeth I, held numerous manors throughout the country including, apparently, Englefield. He also had a town house in Reading, on the corner of Broad and Minster Street. He entertained the Queen there and for many years a plaque on the outside of this rather elegant building recorded her stay. The Earl of Essex used it as his headquarters after the Siege of Reading. Unfortunately, Walsingham House, or Hounslow's Corner as it was later known, was pulled down in about 1905. Its replacement has been likened to a Carnegie Library. It is now a coffee shop. Reading was essentially for Parliament during the Civil War, and was originally garrisoned, in 1642, by Henry Marten MP, Lord of Hinton Waldrist and several other North Berkshire Manors. However, with reports of approaching Cavaliers, he quickly abandoned the undefended town. The council had, in fact, been split and some welcomed the Royalist Army that arrived three days later. Reading became the largest Royalist garrison outside Oxford with three thousand soldiers to feed. The town was heavily taxed for this honour, and the council's finances crippled. By the time the parliamentarians decided to besiege Reading though, it was highly fortified. The Earl of Essex made siege to the town for some ten days in April 1643. The gunfire was fierce, but the Roundheads managed to discover plans for Royalist reinforcements from Oxford and headed them off. With no relief force the town's garrison was forced to surrender. During the Siege of Reading, St. Giles' Church, in Southampton Street, had a gun emplacement on top of the tower. Its spire, not unnaturally, did not last very long. It was later replaced by a very elegant slender affair on an octagonal rotunda. The church was completely rebuilt in 1870. In the late 17th century, St. Giles' churchyard was where many of the dead from the Battle of Broad Street were buried. This was when Reading saw the only fighting of the Glorious Revolution of 1688. The people of England wished to rid themselves of the catholic King James II and had welcomed his protestant son-in-law as William III in his stead. As William marched up from the West Country, James held London but sent out an advance guard of several hundred Irish troops to intercept his son-in-law at Reading. The Readingensians were terrified of the catholic Irishmen who they believed would massacre them in their beds rather than give up the town. They managed to sent out messages to William at Hungerford warning of the catholic strategies. Thus, when his Dutch army arrived they easily routed the Irish. Pushing them back from their posts in Castle Street and St. Mary's Churchyard, the main body of men in the Market Place fled in the confusion. The Sun Inn in Castle Street is the most fascinating of Reading's old pubs. It has a Norman archway which once led to a large underground hall. The place was probably an hostelry as far back as the 13th century. Five hundred years later it was a popular coaching inn. The undercroft could house up to fifty horses. It had already been home to prisoners awaiting execution from the gaol next door, and Napoleonic prisoners of war followed. Sadly this underground room collapsed in 1947 after being damaged by circus elephants tethered down there two years previously. The Oxford Arms in Silver Street also had penal connections. The Reading hangmen would stop here for a drink with their victims before they were led to Gallows Tree Common in Earley. Reading has been home to numerous distinguished inhabitants. Anthony Addington was an 18th century doctor who lived in London Street (there is a blue plaque). His mental patients lived next door. He attended the infamous murder, in Henley, of Francis Blandy (2nd cousin of the first Reading solicitor's father) by his daughter, Mary; and later, through his friendship with the Pitts, he was appointed physician to the mad King George III, who recovered for a while under his watchful eye. His son, who lived at Woodley Lodge, became Prime Minster. Before she moved to Grazeley in 1806, Mary Russell Mitford lived, with her parents, in the London Road, in the fine mansion opposite the end of Kendrick Road: a plaque on the wall records her residence. Mary was an author, famous, not only in Berkshire but throughout England and America, for writing such works as Our Village and Belford Regis. Her father was a hopeless gambler and poor Mary was obliged to write to keep the family together. The Reading house was even bought with the £20,000 winnings of an Irish lottery ticket which Dr. Mitford had bought for his daughter! Belford Regis was, in fact, a thinly disguised view of Reading itself, which has also featured elsewhere in great literature. Thomas Hardy called it Aldbrickham in Life's Little Ironies. Sam of The Son's Veto had a fruitier's shop in the town. Later, in Jude the Obscure, Reading (or Aldbrickham) appeared again as the home of Jude and Sue, and their monumental masonry business.

Joseph Huntley moved to Reading in 1811 and he and his son, Thomas, took on 72 London Street (another plaque), as a bakery, eleven years later. They cashed in on the coaching trade of the Crown Inn, opposite (but long gone), by sending over freshly baked biscuits for travellers to buy. Another son, Joseph, set up an ironmongery and whitesmith's shop (later Huntley, Boorne & Stevens), and began making them fancy biscuit tins. George Palmer, the famous Reading benefactor, joined the bakery in 1841, and hence it became Huntley & Palmers, long World famous for their biscuits. The vast factory, off the King's Road, dominated the town for over a hundred years. It closed in 1976 and has been all but swept away. Though the name is still used, the firm, having undergone a number of changes in ownership, now operates on a much smaller scale out of Suffolk. Biscuits completed Reading's Three Bs. The two earlier foundations being for beer & bulbs (plants not light-bulbs). William Blackall Simonds had founded the Simonds' Brewery back in 1785. (Banking should perhaps have been the third B, for he also launched the Simonds' Bank with his cousins not long afterwards: the brass plaque bearing the family name clung to Barclays Bank in King Street until it closed in 2009). The original brewery at the top of Broad Street, but very quickly moved to Bridge Street with Simonds' home standing at the centre, both having been designed by his friend, Sir John Soane, the architect. The old name of 'Seven Bridges Street' indicates how wide the Kennet Bridge once was and how many streams the river split into. The Simonds' business was famous for its hop leaf symbol until taken over by Courage in 1960. Courage dropped the Simonds name after ten years and, in 1985, moved to a vast new brewery, the largest in Europe, down by the M4. The old brewery was pulled down to make way for the Oracle Shopping Centre and new one followed in 2010. The business was wound up and the brands sold to a small Bedford brewery. The bulbs, Sutton Seeds, started as a corn merchant's in 1807 and later specialised in seeds under Martin Hope Sutton. Their fine building in the Market Place - more spectacular still than the surviving NatWest Bank a few doors down - was pulled don in the 1960s. There was a vast complex behind all the shops that went right through to a grand arch in the Forbury. The company moved out of the town to Reading in 1976, but is still prominent in the seed world. Another great commodity for which Reading was famous in the Victorian Age was Reading Sauce. Very like Worcester Sauce, it was even more popular in its day. Sadly the demand gradually declined this century and the company eventually went bust. See also Whitley, Tilehurst, Earley, Woodley & Caversham Click for Map

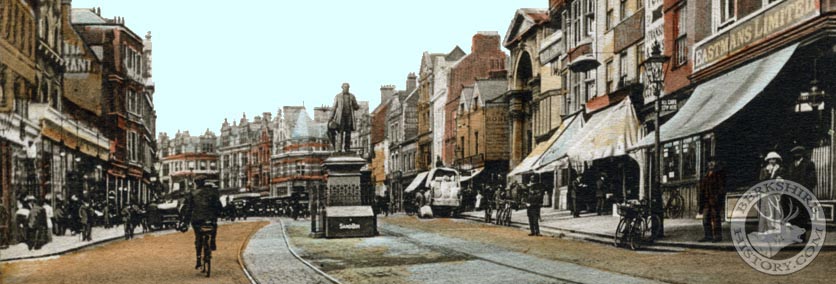

of Victorian Reading

|

|||

| © Nash Ford Publishing 2001. All Rights Reserved. | ||||

It was while staying

at the Abbey, the previous year, that Henry II had witnessed the

It was while staying

at the Abbey, the previous year, that Henry II had witnessed the  Near

to the first Guild Hall stood

Minster Mill, both for corn and fulling in Queen Elizabeth I's time. It stood on the

site of one of six Domesday mills. St. Giles' Mill in Mill Lane, with huge associated

Near

to the first Guild Hall stood

Minster Mill, both for corn and fulling in Queen Elizabeth I's time. It stood on the

site of one of six Domesday mills. St. Giles' Mill in Mill Lane, with huge associated  In the early 1840s, the Father of Photography, William Fox-Talbot,

set up the first mass production photographic laboratory in Russell Terrace.

Another plaque records this. He was producing the first book of photos, but

the locals thought his assistants were forgers! William Penn, founder of

Pennsylvania, had connections with Reading. He attended the old quaker

meeting house on the site of the classical-temple-looking hall-cum-church, now a pub, in London Street and his ghost

was said to haunt the old London Street Bookshop next door. Another

well-known resident was Oscar Wilde who was imprisoned in Reading Gaol for

two years in 1895 for his social indiscretions. He never wrote again, save

for his Ballad of Reading Gaol.

In the early 1840s, the Father of Photography, William Fox-Talbot,

set up the first mass production photographic laboratory in Russell Terrace.

Another plaque records this. He was producing the first book of photos, but

the locals thought his assistants were forgers! William Penn, founder of

Pennsylvania, had connections with Reading. He attended the old quaker

meeting house on the site of the classical-temple-looking hall-cum-church, now a pub, in London Street and his ghost

was said to haunt the old London Street Bookshop next door. Another

well-known resident was Oscar Wilde who was imprisoned in Reading Gaol for

two years in 1895 for his social indiscretions. He never wrote again, save

for his Ballad of Reading Gaol.