|

|

|||

|

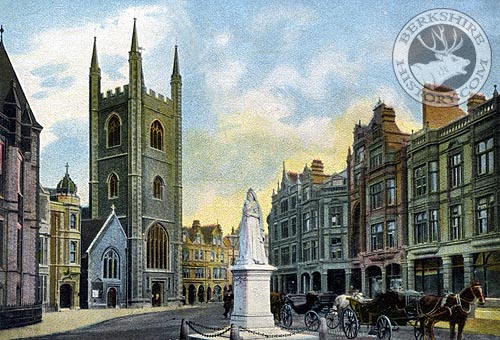

The name Friar Street refers to the Franciscan ‘grey’ friars who established their friary at, what is now, No. 65 Friar Street in 1285. The name was first adopted sometime after the Dissolution, certainly by 1714. Previously, it had been called New Street, first recorded in 1224 but dating from the 1120s when the street was first laid out, running westward from the northern edge of a new Market Place set up by the monks of Reading Abbey, soon after its foundation. The western end of the road, past the West Street junction, was often known as Town’s End, clearly indicating the Norman extant of Reading in that area. At this point, the triangle formed by Friar Street, Caversham Road and Lower Thorn Street, was the site of the Chapel of St. Edmund. It was founded on behalf of Reading Abbey in 1204 by Laurence Burges, an early member of a well-known Reading family. Burges retired from public life to become a hermit in the adjoining cell. However, the abbey withdrew their support in 1376 and the chapel became a barn, before eventually being demolished. Features The most recognisable part of Friar Street is its eastern end, around St. Laurence’s Church, now a pedestrianized open area with seating and greenery around the statue of Queen Victoria. St. Laurence’s is one of the three ancient churches of Reading, built by the monks of Reading Abbey in the 1120s to serve the shopkeepers they were busily trying to attract to their new market place, immediately to the south. The original small chapel of St. Laurence was rebuilt in 1196 and again in the 1440s to form the large building we know today. It was the mayoral church, always popular with the rich merchants of the town. Immediately adjoining on the west side is No. 1 Friar Street, the home of the well-known Reading solicitors, Blandy & Blandy, since 1798. The current building was built after the previous Victorian-Gothic extravaganza (by Albury 1875) received a direct hit from a German bomb on 10th February 1943. St. Laurence’s was also damaged in the explosion and the southern tower of the Town Hall was destroyed and not replaced until 1989. Queen Victoria’s Statue stands in front of these buildings. It was sculpted to celebrate her Golden Jubilee (1887) by the famous son-of-Reading, George Blackall Simonds, of the brewing family. Popular local legend suggests that her Majesty cancelled a planned visit to Reading and never rescheduled, so her statue was erected with her back to the town in order to remember the snub. There is no evidence for this story. She simply faces the great and the good of Reading as they leave the Town Hall and head into town. Across the road from the St. Laurence’s is the rather plain Bristol and West Arcade, now sadly dilapidated and empty of shops. It began life as the Market or Fidler’s Arcade. JC Fidler of Fidler and Sons’ Royal Berkshire Seed Stores, at the other end of the street (Nos. 107-109), was a highly successful businessman and councillor who financed this and other construction projects in the town at the very start of the 20th century, including the building of Queen Victoria Street. The entrance was once a grand and imposing example of Reading brick and terracotta work. Sadly the adjoining People’s Pantry (formerly Gregory & Love’s Grocery Store), like Blandy’s opposite, was hit by a German bomb on 10th February 1943, killing over twenty people. The arcade entrance was left unsafe and had to be demolished soon afterwards. The best surviving brickwork in the street is now at the old YMCA on the corner of Merchant’s Place (1897), and currently called Ajilon House.

The Central Cinema was opened at No. 25 Friar Street in 1921. This magnificent Art Deco or ‘New Greek’ building was designed by George Gardiner of Oxford. It was demolished in 2002. The first Reading Theatre had been opened by Henry Thornton at No. 121 Friar Street in May 1788. It lasted until 1868, when the (Theatrical) Assembly Rooms opened a little further east at Nos. 126-8, next to the ‘Marquis of Lorne’. They burnt down in 1870, but were quickly rebuilt as the Theatre Royal and Albert Hall (& Royal Berkshire Skating Rink!). While leased to music retailer, Frank Attwells, in 1887, it became known as the Royal County Theatre, but burnt down again in 1895. The old Augustine Chapel, a few doors down at No. 113, which had only been converted into the Princes’ Theatre two years before, was renamed the New Royal County Theatre to take its place. This too eventually burnt down in 1937. The theatres did not have the best of reputations in their early years, hence they were built at the less salubrious western end of the street. The rather attractive Blagrave Buildings - ‘model dwelling houses’ or tenement block – were erected to provide decent housing in this area in 1867. They were pulled down in the 1960s. Pubs are again prominent in the street today as they were in the past, although the locations have moved and only the Bugle remains as a site of any antiquity. Prominent pubs now gone include the Star & Garter, the Marquis of Lorne (later the Tudor Tavern), the (sadly missed) Boar’s Head, the Wheatsheaf and the Queen’s Hotel which was replaced by the new Post Office in 1923, but the site now a pub once more. A Primitive Methodist Chapel (between No.70 & 71) was built on the corner of Thorn Street, and the Augustine Chapel, already mentioned, was briefly at No. 113 before convertion into the Princes’ Theatre. The remains of the Greyfriars’ Church were restored as a C of E church in 1863. It had previously been the town prison for many years (as described by John Man in 1808) and, in Tudor times, briefly, the Town Hall. Next door is the old vicarage, largely rebuilt in 1961, though its basis is a John Soane house of 1796. With the arrival of the Railway in 1840, the focus of Reading shifted towards the Station and Friary Street flourished. Through the late 20th century Georgian offices were replaced with retail shops, some of them being ruthlessly torn down. Since the opening of the Oracle Shopping Centre in 1999, the focus of the town has moved back towards the Kennet, unfortunately to the detriment of Friar Street. Historic well-loved buildings, like the Victorian Boar’s Head and the Art-Deco Cinema, continue to be demolished and replaced by hideous post-modernist hotels and supermarkets. As the Yale Pevsner Guide remarks, “Friar Street continues west from the corner with station Road, falling off architecturally”.

|

|||

| © Nash Ford Publishing 2016. All Rights Reserved. | ||||

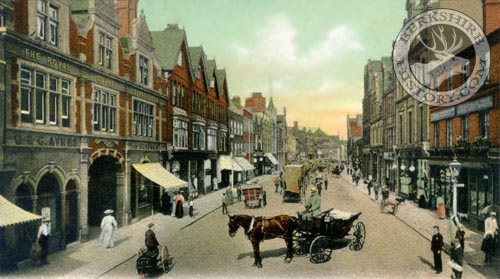

The attractive Harris Arcade was built through a Georgian house at No. 15 Friar Street in 1929. This was the respectable end of Friar Street. Next door, of the same era, had stood “the best example of a town house of its period in the Borough” at Nos. 16-17, until pulled down in 1955. It was one of several old town houses popularly built by the rising classes in Eastern Friar Street, that later became offices of insurers, solicitors, surgeons, auctioneers, architects (such as Brown & Albury who were at No. 154) and the like. A few still survive, but others are 20th century imitations. Here too were the similarly occupied Laud Chambers and Gentlemen’s clubs, like the Wellington and the Athenaeum. This area was also well known, from the Georgian through to the Edwardian period, for its music shops: Frank Attwells’ at Nos. 162-3 (behind Victoria’s statue), Binfield’s Corner (1799) at No. 159 (the junction with Cross Street, after 1902 the bespired Gas Showroom) and, of course, Hickie’s (1864) which still occupies No. 153 today. Other well-known Friar Street shops of the past include Arthur

Newbery’s Furniture Store at Nos. 146-147, the back entrance to AH Bull’s Drapery at Nos. 118-119 and Langston & Sons’ Outfitters at No. 93 on the corner of West Street. Amongst the non-retail businesses were Tomkins’ Royal Horse & Carriage Repository, behind much of Station Road and Friar Street and with the entrance at No. 25; and C & G Ayres coal & coke merchants (1825) at Nos. 44-47. The latter eventually moved into general removals and now operate from Ross Road.

The attractive Harris Arcade was built through a Georgian house at No. 15 Friar Street in 1929. This was the respectable end of Friar Street. Next door, of the same era, had stood “the best example of a town house of its period in the Borough” at Nos. 16-17, until pulled down in 1955. It was one of several old town houses popularly built by the rising classes in Eastern Friar Street, that later became offices of insurers, solicitors, surgeons, auctioneers, architects (such as Brown & Albury who were at No. 154) and the like. A few still survive, but others are 20th century imitations. Here too were the similarly occupied Laud Chambers and Gentlemen’s clubs, like the Wellington and the Athenaeum. This area was also well known, from the Georgian through to the Edwardian period, for its music shops: Frank Attwells’ at Nos. 162-3 (behind Victoria’s statue), Binfield’s Corner (1799) at No. 159 (the junction with Cross Street, after 1902 the bespired Gas Showroom) and, of course, Hickie’s (1864) which still occupies No. 153 today. Other well-known Friar Street shops of the past include Arthur

Newbery’s Furniture Store at Nos. 146-147, the back entrance to AH Bull’s Drapery at Nos. 118-119 and Langston & Sons’ Outfitters at No. 93 on the corner of West Street. Amongst the non-retail businesses were Tomkins’ Royal Horse & Carriage Repository, behind much of Station Road and Friar Street and with the entrance at No. 25; and C & G Ayres coal & coke merchants (1825) at Nos. 44-47. The latter eventually moved into general removals and now operate from Ross Road.