|

|

|||

|

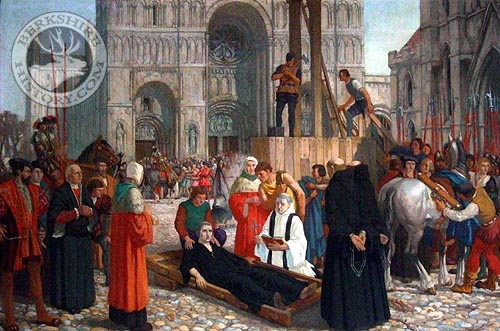

The Fall of the The Fall of theAbbot of Reading and his Great Abbey Having taken control of the new Church of England, King Henry VIII turned to the English & Welsh monasteries in his search for money to fill the Royal coffers. By the end of the year 1536, most of the lesser monasteries had been dissolved, as a result of the report of two Royal Commissioners, known as the ‘Black Book,’ which had been laid before Parliament, and had charged the religious houses with all kinds of immorality. Their assets now belonged to the Crown. The larger houses, which had, on the whole, been better conducted, remained intact, for the Act of 1536 only contemplated their passing into the King's hands in the case of voluntary surrender. Even the attainder of an Abbot for treason had not hitherto involved the confiscation of the Abbey over which the attainted superior ruled. But, after the Northern Rebellion had been subdued, this victory was used as a pretext for further suppressions and the King determined to confiscate the property of a corporation, where its head had been attainted of treason. This was not, strictly speaking, legal. But in order to meet such cases, a clause was inserted in the Act of April 1539 covering the illegal suppression of the greater monasteries, and granting to the King all "Abbathies, Priories etc., which hereafter shall happen to be dissolved, suppressed, renounced, relinquished, forfeited, given up or come unto the King's Highness." There is also a parenthesis referring to such others as "shall happen to come to the King's Highness by Attainder or Attainders of Treason." This Act passed the House of Lords without protest on the part of any of the Abbots, although those of Glastonbury, Colchester and

Reading, and others were present. It seems clear, therefore, that, at this period, there was no suspicion of the storm that was so soon to overwhelm these three great prelates, although the Act dealt with the very attainder for treason under which, a few months later, they were executed. The Venerable Hugh Cook of Faringdon was especially loyal to the Vicar of Christ, declaring that he would "never in his heart accept the King's supremacy, but week by week would offer the holy sacrifice on behalf of the Bishop of Rome, and call him Pope till his dying day." While Cromwell was preparing his case against the Abbot, another was on the look-out for a share of the rich spoils to be derived from Reading Abbey. This was Sir William Penizon, who actually resorted to bribery to gain his purpose. His letter survives, asking for the receivership of the Abbey. "I present," he writes to Cromwell on 15th August, "unto your lordship a diamond set in a slender gold ring, meet to be set in the breast of a George, which, though not of the best, he desires Cromwell to accept, reminding him that he moved Cromwell not long agone of the dissolution of Reading Abbey"; and that "the Abbot, preparing for the same, sells sheep, corn, wood, etc to the disadvantage of the King, and partly also of the farmer." Seven years later, it was claimed that, seeing the storm likely to break out, the Abbot had sent a great deal of his plate and money to the rebels in the north. This being afterwards discovered, he was attainted of high treason the following year. As a Peer of the Realm, Hugh Faringdon ought to have been arraigned for treason before Parliament, but no trial under attainder took place, and his execution was over, before Parliament came together. As a matter of fact, no proper trial of any kind took place, and he was condemned to the death of a traitor as the result of secret inquisitions in the Tower of London by a tribunal that had no jurisdiction. Indeed, there is evidence that Cromwell, acting as ‘prosecutor, judge and jury,’ had determined on the Abbot's death before he left the prison, for in Cromwell's ‘Remembrances,’ written down with his own hand, we read: "The Abbot Redyng to be sent down to be tried and executed at Redyng with his ‘complices," proving that the ultimate issue had been determined beforehand. Brought down from the Tower to Reading, on his last tragic journey, Faringdon underwent, in his own hall of justice, what was nothing more than a travesty of justice. But even the prospect of a felon's death could not daunt his heroism. True to his conscience, he chose death rather than dishonour. A traitor's death was accompanied by every ignominy. First came the stretching of the limbs on a hurdle, which was dragged about the town by a horse. Then the last pathetic scene, when Faringdon, standing before the Inner Gateway of his stately Abbey, with the rope about his neck, and on the verge of eternity, addressed the crowd that had flocked to witness the execution of the great lord Abbot. As for the monks, they were expelled from their well-beloved sanctuary, and cast adrift in the World. There is no record in the Books of the Augmentation Office of any pension being granted even to those monks who, from infirmity or old age, were incapable of earning their livelihood. Not until fifteen years later, in 1554, were thirteen pensions and one annuity given to monks who were still alive and made application. Edited from JB Hurry's "Reading Abbey" (1901)

|

|||

| © Nash Ford Publishing 2017. All Rights Reserved. | ||||