|

|

|||

|

Minster Street is probably one of the oldest streets in Reading. The town grew up in Saxon times around the Minster Church of St. Mary, alongside the main road from Southampton to Oxford, although the name is only first recorded in the 13th century. The street name probably originally stretched from the south-west corner of St. Mary’s churchyard up both Gun Street and Minster Street heading north-east probably towards the location of the Royal estate that the king held in the town from at least the reign of Edward the Confessor. In medieval times, the northern end of the street, up from the Yield Hall Lane (now Place) junction, was called Tot Hill, indicating the site of an Anglo-Saxon lookout point, perhaps even a tower. Later, in the 1120s, the monks of Reading Abbey built Broad Street and what became known as King Street across this northern end of the street. The lower end may have become known as Gun Street after the Civil War. Today the street’s numbering starts at No 1 (aka 134 Broad Street), standing on the north-west (Hounslow’s) corner, and runs along the north side of the street to what was originally No 35, but was renumbered as No 30 in 1902, on the corner of Chain Street at the south-west. No 31 (pre-1902 No 36) is across the road at the south-east corner and the junction with what was previously called Gun Passage, but is now just part of the Oracle Shopping Centre. The numbering continues along the south side of Minster Street, returning up to No 64 (aka No 8 King Street) at the north-east (Horniman’s) corner. The shops in this last section have now gone and the buildings form part of the George Inn, which still retains the Minster Street entrance to its attractive courtyard. The southern premises in the street back on to the Holy Brook which can still be seen in the open as one passes from Gun Passage into the Oracle Shopping Centre. For details of Walsingham House & Hounslow’s Corner, please see our history of

Broad Street; Features Today, Minster Street is a very quiet street. Its buildings are the backs and sides of premises with their main entrances in the surrounding streets, notably the Oracle Shopping Centre with its large pedestrian fly-over. There are only two small shops, apart from the Minster Street entrance to John Lewis’ (aka Heelas’) Department Store, and the Citizens’ Advice Bureau and the Telephone Exchange. It is very different from its heyday. At one time, Minster Street was, along with Broad Street, the main shopping street in Reading. However, with the opening of the Railway in 1840, the town’s epicentre shifted towards the Station, and Minster Street lost out to Friar Street. It was still important in the Victorian era, but gradually declined in the 20th century.

At one time, there was a medieval stone preaching cross called 'Gerrard's Cross' (perhaps named after the Garrards, a well-known West Berkshire family) somewhere in Minster Street. By 1311, the town’s dominant cloth industry had established its market in the area of Nos 5-6 on the north-west end of the street, and, from at least 1420, Minster Street led through to the town’s Guildhall, down Yield Hall Lane. Hence Minster Street quickly grew in importance. However, the most well-known feature of Minster Street in times past was the handsome Oracle Workhouse that stood on the Gun Passage corner, on the old kitchen site, from 1628 until 1850. It was founded under the will of John Kendrick, a rich London cloth merchant who had grown up in his father’s house on the site. This had been a busy cloth-working factory until turned over to the Workhouse by Kendrick’s brother and extended. It had originally been surrounded by tanneries making good use of the water from the Holy Brook. Even after the workhouse faltered, the Oracle survived as a centre of manufacturing, especially for pin and rope making. There were rope walks to the south of the Holy Brook where the ropes were twisted. The place was finally pulled down in 1850 and replaced by retail shops known as St. Mary’s Parade. This took up Nos 36 & 37, but this end of the road was renumbered in 1902 so that each shop in the parade could have a number from 31 to 37. The new numbers were taken from across the road where Heelas stretched all the way from No 24 to what was then No 34. Not all its numbers were needed, so this was reduced to Nos 24-29, with just a single different shop on the corner with Chain Street. Rope making continued in Minster Street when, about 1860, John Swain, who ran a rope, brush & basket making business at 127-8 Broad Street, took on a second shop at No 18 Minster Street, moving to No 16 about six years later. Apart from John Kendrick, there were other well-known characters associated with Minster Street. Sir John Barnard, the 18th century politician & Lord Mayor of London, was born somewhere in the street in 1685; as was William Robert Grossmith, a famous child actor in the 1820s, in 1818; while No 11 had been the Glove Shop of James Noon (1786-1861), the maternal uncle of the Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, Thomas Noon Talfourd (1795-1864). The family came from Hungerford. James was also a ‘breeches maker’ and retired in March 1852, having been in business for over fifty years. Minster Street was well known for its many popular inns in the Tudor and Stuart period, and beyond. Opposite the Oracle, in Minster Street, had stood the Rose Inn at No 15. In the early 20th century, the name was reinstated at No 2, which had previously been Wellman’s Wine Vaults for many years. Victorian pubs included the Plough Inn at No 20, the Eagle (previously the Falcon) at No 30, the Queen’s Head (also known as the Pelican and then the Reindeer) at No 34 7 the London at No 46, all except the last on the north side of the street. The Tudor ‘Cardinal’s Hat,’ at No 15 was a particularly well-known meeting place. Geoffrey Gunter, the servant of Sir William Essex of Lambourn Place & Beckett Hall, copied the subversive Aske's Manifesto, opposing Henry VIII’s religious policies, at the inn and caused a scandal when further copies started to spread around the town. Later, in the reign of ‘Bloody’ Queen Mary, the Puritan martyr, Jocelyn Palmer, was arrested there and later burnt to death in Newbury.

Robert Snare (1758-1838) had first established his bookshop at No 16 in 1790, initially specializing in ecclesiastical books. His shop was also briefly described by John Man in 1808. Snare's brother, John (1770-1834), was a haberdasher at No 21, followed by John’s youngest son, William Henry (1815-1848), who expanded their range as a hardware store & fancy emporium. John’s eldest son, another John (1808-1883), joined his uncle, however, at Snare & Nephew, Booksellers, Bookbinders, Stationers & Printers from 1834. Robert Snare died four years later and John then added a lending library to the business. As well as the usual visiting cards and handbills, Snare printed fine publications, such as his, now rare, ‘Tour round Reading & its Environs’ (1843) with very early printed engravings. He also sold stationary of various kinds, and prints of famous paintings. Snare had a particular interest in art and, in 1845, purchased a fine portrait of the young King Charles I from an auction at Radley Hall. He exhibited it, for a small entry-fee, in a back room at the shop in Minster Street and then in London, attracting such admirers as Mary Russell Mitford and the Duke of Wellington. He declared it, on good grounds, to be a lost Velazquez, but the opinions of art historians were divided. He poured all his money and energies into preserving and promoting the painting, but he was almost ruined when the Earl Fife tried to claim possession and took him to court in Edinburgh. Snare eventually won the case but was forced to abandon his family in Reading and flee to New York in order to avoid more trouble. He lived there for almost forty years, still exhibiting the painting on occasion, but never returned home. The street continued to be popular with booksellers throughout the late 19th century: JG Wyly’s Bookbinding Establishment & Account Book Manufactory (later Knill & Son who owned the John Read Print Works at 22 King’s Road) at No 2 St Mary’s Parade; and, Frederick Golding at No 10. The hardware store of Snare’s brother at No 21 adjoined the lane which became the back gate to Ferguson’s Brewery (in Broad Street), between this and No 22. In the early 19th century, the Trendell family dominated Minster Street. No 22 had been the Pork Butcher’s Shop of Thomas Trendell (1776-1866) from Hurst. By 1837, the business was called Trendell & Son and a second shop was open at 115 Castle Street a few years later. His son George (1810-1882) became a jeweller in Maidenhead High Street. Another son, Edwin James (1811-1900) became a wine merchant in Abingdon. Thomas’ brother, Henry (1766-1848), was four doors up the road from him, running a ladies’ and gentlemen’s hairdresser’s & perfumery at No 18 Minster Street. He moved there from Friar Street in 1791, apparently with his brother, James (b. 1761), although he quickly went into a partnership with William Pickett that lasted for the next four years. Henry later concentrated on the perfumery and, in 1827, passed his hair-dressing department to Thomas’ other son, William Henry (1803-1888). He had trained at Lewis’ in Manchester and, three years later, moved to more commodious premises at No 62. Henry’s own son, another James (1790-1866), became a gold & silversmith, watch & clock maker, jeweller & engraver, under Charles Packer (1747-1808) at No 55 which had been established there 1789.

From the 1940s, Bracher & Sydenham had also dealt in antique silver and jewellery. At No 31 (previously No 35) was another Antique Shop, specialising in furniture: Arthur George Negus’ which was taken over by his twenty-year-old son of the same name upon his death in 1923. The shop was on the corner of Minster Street and Chain Street until finally swallowed up by Heelas in the mid-1930s. Arthur Negus (Junior) went on to be a popular antiques expert on television shows of the 1970s and 80s. The Heelas brothers had opened their drapery at 33 Minster Street, near the Chain Street corner, in 1854. It quickly expanded to No 32 next door, and then to an old chapel (see below), when they added carpets and cabinets to their repertoire, followed by all manner of household furnishings, until it became the department store we know today. By 1870, the shop had broken through to Broad Street which subsequently became the building’s main entrance. Nearly 30 years later, the original shop was replaced by a fireproof depository, followed by further expansion into adjoining premises and rebuilding. The present Minster Street end of the building was built in 1979 by the RD Cook Partnership to designs by Sir Hugh Casson. Heelas also had a garage and furniture warehouse in Earley Place which, during World War II, received a direct hit from a German bomb on 10th February 1943. The Heelas name was dropped in favour of its John Lewis owners in 2001. From about 1750, there was a small non-conformist chapel at Nos 28-29 Minster Street called the Salem Chapel. This was actually located in the Salem Yard or Court, behind No 31, and accessed via Salem Place, a small ‘court’ between Nos 27 & 30. It was built for the Presbyterians when they moved from Sun Lane, but the establishment was wound up in 1780. In 1808, part of the congregation of St. Mary’s Castle Street merged with the Hosier Street Baptists and they moved into the old chapel as a new Congregational Church. However, they only stayed until 1820. It was subsequently occupied by the High Calvinists and then the Primitive Methodists. The latter moved to the New Hall (aka ‘Great Expectations’) in London Street in 1866, when Heelas expanded to cover this area. Its remains were finally demolished in 1900, although one wall survived for some time as part of Heelas’ carpet department. Minster Street originally had seven residential ‘courts’ shooting off it, such as China Court (behind No 13), Silk Court (heading to the mill, behind No 50) and Moule Cottages (behind No 43 over which there was a serious land dispute in 1874). Earley Place, leading to Earley Court originally called ‘Johnson’s Yard,’ was main court in the street. It ran along the eastern boundary of the old Oracle. Here Griffin Jenkins left five tenements to the Corporation for the rent-free residence of five poor aged men in 1624. On the corner of Earley Place corner stood the old Foundation School, at Nos 38-40 Minster Street, from 1766. It was founded by Rev. Fox of St. Mary’s using money invested in South Sea stocks and left for the purpose by a certain James Neal of Gray’s Inn in 1705. The school could support up to twenty-six pupils. The building was originally associated with the Oracle complex and largely of similar date, having “in the room next to the street… some old carved wainscotting… and there [was] a chimney piece in the apartment behind, of a still more remote date.” From at least 1826-1851, the adjoining property, No 41, was the ‘original’ clog and patten manufactory and grindery warehouse of William Attwell (1799-1873), skilled in an almost lost art of times past. There seems to have been little demand for his wares even then. George Emery once had a similar business two doors down, at No 39 (later Arthur Lewis’ Reading Photographic Studio), but had to turn to general carpentry. William eventually went bust in 1849, but does seem to have subsequently recovered his business for a few years. The site of these shops and that of the old school is now occupied Telephone Exchange, built in 1903 by Leonard Stokes.

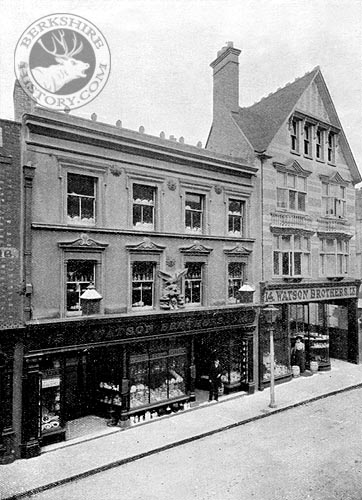

In 1884, it was reported that “Minster Street is not one of the principal business streets now”. By 1892, it had become “the narrowest carriageway in the town,” particularly at the two sharp corners on the bend opposite the Yield Hall Lane junction. These were considered quite dangerous to manoeuvre around, as it was very difficult for two vehicles to pass one another. The plate glass windows of Bracher & Sydenham’s Jeweller’s had been smashed five times, and, for the previous fifteen years, the

Simonds’ Brewery had had to make arrangements for their drays to avoid holding up the traffic in Minster Street, by travelling the long way round via the Butts & Broad Street. This was the start of the decline of Minster Street. There were grand plans to fix the situation which, however, were not universally popular. Wellsteed’s Department Store, which had arrived in Broad Street in 1861, had recently purchased No 9 Minster Street and were expanding their shop through to this entrance. They sold a small piece of land to the Corporation who then had to purchase all of Nos 4-8 & 10-12. They pulled them all down and the street was widened as planned with a new smooth sweep around the bend. The scheme cost over £17,000 (over £1m today). The rear of the Wellsteed’s building later expanded across the demolished shops and became its restaurant. Like Heelas’ yard, it famously received a direct hit from a German bomb on 10th February 1943. Wellsteed’s later became Debenham’s.

|

|||

| © Nash Ford Publishing 2017. All Rights Reserved. | ||||

Early in its history, the street was the home to several

Early in its history, the street was the home to several

By about 1753, the Cardinal’s Hat had become a China Shop.

In the 1794, James Rusher opened a shop in Castle Street, selling a bizarre

mix of Stationery and China & Glass. However the following year, he

wisely divided the business into two branches: opening a bookshop &

lending library in King Street and a second branch, a Staffordshire China

& Glass Warehouse at the old China Shop at No 15 Minster Street. He

quickly decided to concentrate his efforts on the book & stationery side

of the business, however, and, by 1796, was already looking to let in

Minster Street shop. By the 1810s, James Drover (1762-1816) and his son, James Barlow

Drover (1791-1823), were at the Minster Street China Shop, as

By about 1753, the Cardinal’s Hat had become a China Shop.

In the 1794, James Rusher opened a shop in Castle Street, selling a bizarre

mix of Stationery and China & Glass. However the following year, he

wisely divided the business into two branches: opening a bookshop &

lending library in King Street and a second branch, a Staffordshire China

& Glass Warehouse at the old China Shop at No 15 Minster Street. He

quickly decided to concentrate his efforts on the book & stationery side

of the business, however, and, by 1796, was already looking to let in

Minster Street shop. By the 1810s, James Drover (1762-1816) and his son, James Barlow

Drover (1791-1823), were at the Minster Street China Shop, as  James Trendell took

over the business in 1815 and, nearly forty years later, was joined, as a

partner, by Reuben Bracher (1825-1888) in Trendall & Bracher’s

Jewellery Shop. Trendell retired after just three years and his name was dropped from the business. In 1874,

Bracher joined in partnership with his nephew, Joseph Sydenham (1846-1913) (a founder & first secretary of Reading Football Club), and

James Trendell took

over the business in 1815 and, nearly forty years later, was joined, as a

partner, by Reuben Bracher (1825-1888) in Trendall & Bracher’s

Jewellery Shop. Trendell retired after just three years and his name was dropped from the business. In 1874,

Bracher joined in partnership with his nephew, Joseph Sydenham (1846-1913) (a founder & first secretary of Reading Football Club), and

No 53 Minster Street also had some superb Elizabethan carving in the form of a fireplace surround in the eastern room at the back of the shop, but this was removed and sold in March 1927. Next door, at Nos 51-52, John Henry Fuller (1838-1902) had his

No 53 Minster Street also had some superb Elizabethan carving in the form of a fireplace surround in the eastern room at the back of the shop, but this was removed and sold in March 1927. Next door, at Nos 51-52, John Henry Fuller (1838-1902) had his