|

|

|||

|

|

The Civil War

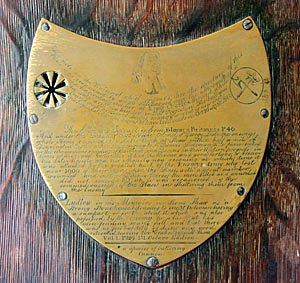

In the wainscot of the south-facing bay window in the former best bedroom, there is, let into the wall panelling, a brass plate perforated at a spot where a bullet-hole may be seen. This is said to have been the work of a Roundhead soldier, who aimed at King Charles I when he was dressing himself at the window, on the morning of the Second Battle of Newbury when the house was heavily under siege. The plate was probably installed by the 18th century historian, James Pettit Andrews, whose father purchased the house when he was fourteen and whose brother, Sir Joseph, lived there throughout his later life. James was very keen on the house's history and persuaded his brother to rename several of the rooms: Queen Anne's Room, the Cromwell Room and this room was (and still is) the King Charles Room. He may also have acquired the Civil War trinkets that were still on show in the house in Victorian times. Unfortunately, the story seems to be totally apocryphal, for Charles was one of the few monarchs who never visited Shaw. During the famous battle, he was kept in Newbury town centre, far from the front line. Andrews was presumably rather quick to accept local oral history; but, who knows, the hole-in-the-wall may really have been shot at a prominent Royalist in the manner described. It just wasn't King Charles.

At the Restoration

of the Monarchy in 1660, Thomas Dolman was knighted and Charles II and his

brother, the Duke of York, visited him at Shaw, where they reminisced about

the battle at which they had both been present. After Charles' death, the

Duke became King James II, but Sir Thomas disagreed with his Catholic

policies and withdrew to country life at Shaw. However, there was a warm

welcome at the house for the King's Protestant son-in-law, William of

Orange, when he visited on his ride from Torbay to London to take the Throne

as King William III. After Thomas' death, the family

spent still less time in London and his son, another Thomas, decided to

upgrade the old Elizabethan house to incorporate the latest architectural

styles, perhaps in anticipation of another Royal visit. He removed the

screens passage and reduced the height of the hall by inserting a suite of

rooms above, forming the existing first storey. He changed the windows so

that the facade was no longer symmetrical. Then covered the walls of the hall

and other rooms with painted oak panelling and created the present grand

exit from the hall, with central doors to a handsome new staircase of

polished oak, not dissimilar to a contemporary example in Kensington Palace.

Sadly, the decorative newel post finials have long since disappeared, but

there is a fine plaster ceiling above featuring profiled busts representing

the four seasons. There was one part of the house which Thomas Junior did

not change, however. The parlour and the 'Old Queen's Room' which had played

such an important role in his family history were kept exactly as they had

always been. Queen Anne did indeed visit the Dolmans on her return from Bath

in October 1703, but she stayed in the plush new apartments rather than the

Old Queen's Room. The state bedstead in which she was

said to have slept

was long preserved in the house. All photographs taken by kind permission of West Berkshire Council

|

|||

| © Nash Ford Publishing 2011. All Rights Reserved. | ||||

The

Refitting of 1700

The

Refitting of 1700