|

|

|

Hamstead

Marshall Park

Hamstead Marshall, Berkshire

Hamstead

Marhsall, just west of Newbury in Berkshire, has always been an important manor in West Berkshire. The remains of three

castle mottes

stand near the parish church. These were the homes of the powerful Marshal family in the 12th and 13th centuries. In Tudor times,

Sir

Thomas Parry

(d. 1560) was given the manor as a reward for loyal service to Queen Elizabeth I during the period when, as a princess, she was kept a virtual prisoner by her sister, Queen Mary. An

old

story

suggests the unmarried Queen knew this old house rather

well.

The widowed mother of the William

Craven, the son of the Lord Mayor of London of the same name, bought the estate in 1620 for her young son. When he grew up, he is said to have fallen deeply in love with Princess Elizabeth, the sister of King Charles I and the dispossessed Queen of Bohemia. In order to win her heart, he decided to build a grand palace for the lady. In detail, it was to be a miniature version of Heidelburg Castle to remind her of the home she had lost. Elizabeth died before construction work even started, but the Earl still pushed the project onward and, in 1663, began to erect the building as a monument to her memory.

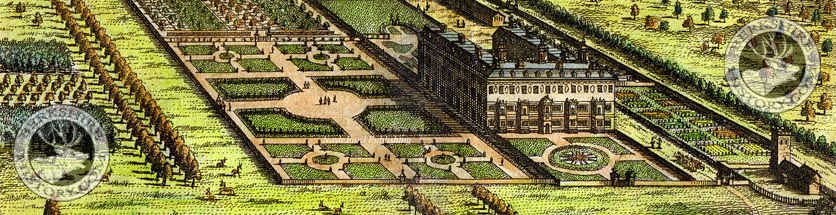

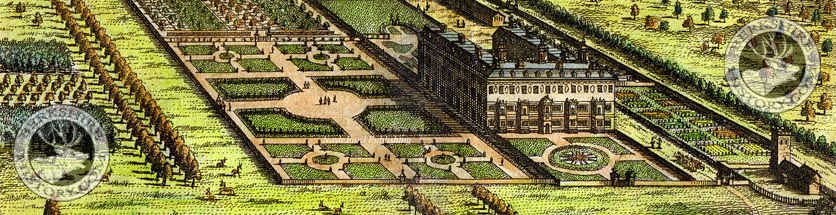

Sadly, the magnificent Carolingian palace at Hamstead Marshall was destroyed by fire in 1718, with the exception of some superb gate piers. However, luckily, Jan Kip made an engraving of it in 1707 which he published in his “Britannia Illustrata”. The extant gate piers stand scattered in a field or leading into a walled

garden, behind the parish

church. The chief pair were moved to Benham Park

and can now be seen along the Bath Road there. It is only when the imagination restores the walls at Hamstead that once connected them that an idea is formed of the size of the original vast enclosures to which those piers were the only entrances.

There are also about forty drawings of detailing in the Bodleian Library, including windows, gate piers, doors and a ceiling. The windows and piers can be identified on Kip's engraving, as also can the general layout, thus confirming the accuracy of Kip's view. His illustration shows the house with a front of Jacobean design in the two lower storeys of its entrance front, but of later character in the third storey and wings. The windows of this later work agree in general appearance with the drawings at the Bodleian, which show festoons above the windows and panels between them, decorated with Lord Craven's cipher, WC, and a baron's coronet. By examining Kip's view in the light of the principal facts of Lord Craven's life, and of the dates on the Bodleian drawings, a shrewd guess can be made as to the history of the house.

In his youth, William Craven achieved such honour through “valiant adventures" in Germany and the Netherlands under Henry, Prince of Orange, that in 1626, when he was eighteen years old, he was knighted by Charles I at Newmarket and was immediately afterwards created a baron, with the title of Lord Craven of Hamstead Marshall. In 1631, he returned to the scenes of his early glories, commanding the English forces attempting to retrieve the Palatinate for the King of Bohemia. He met the Queen in the Hague the following year and thence continued to reside abroad, either fighting for or attending upon the Bohemian Royal family at their court in exile, until the English Restoration. Although absence prevented him from fighting for Charles I during the Civil War, he was a staunch loyalist and helped the king with considerable supplies. This brought him under the notice of the Parliament and his estates were confiscated in 1651, and sold to different persons. After the Restoration, however, Charles II created him an earl in recompense for his services, and he must have quickly regained possession Hamstead Marshall since the drawings for the new work bear a baron's coronet and various dates of which the earliest is 1662.

It would appear, then, that the original house was a Jacobean building, and from the fact that Lord Craven was a bachelor and was resident abroad for the greater part of his life previous to the Restoration, it is highly improbable that he did any building during that period he had neither family nor leisure to induce him. The Jacobean house was therefore almost certainly erected by

Sir Thomas Parry Junior (1544-1616) in the last ten years of his life, after having returned from his embassy in Paris.

On the sale of the Craven property in 1651, it is quite possible that the house was partly dismantled, as were many others in similar circumstances, notably Holdenby House (Northamptonshire);

or, more likely, it was ruined by the Parliamentary troops stationed in the park during the

1st Battle of Newbury. This conjecture is strengthened by a reference of John Evelyn's, who notes that in going from

Reading to Marlborough in June 1654, he saw "My

Lord Craven's house at Causam [ie

Caversham] now in ruins, his goodly woods felling by the rebels."

On his return in 1660, or as soon afterwards as he could, Lord Craven must therefore have set about restoring his estates. At Hamstead, he preserved the Jacobean frontage, but commissioned the disgraced Royal Master of Ceremonies, Franco-Dutchman

Sir Balthazar Gerbier, to build him a magnificent new mansion beyond and above, adding new sides wings and a new top storey. In the Bodleian, is a drawing dated 1662 of the forecourt screen and portico, not unlike that at Castle Ashby (Northamptonshire), which would have formed the back

(or west front) of the house shown by Kip. Drawings of the gate piers in the front wall are dated 1663, and those in the circular wall at the rear 1673. A ceiling, dated 1686 on its drawing, is of the type prevalent throughout the greater part of the 17th century, and usually employed by Inigo ]ones, John Webb and Christopher Wren. The baron's coronet indicates that the work was done before the earldom was bestowed, which was in 1663. The dates on the drawings suggest what one might expect, that the house itself was first taken in hand, then the garden walls and layout, and subsequently the embellishment of some of the chief rooms.

Gerbier unfortunately died on site in 1667 before the first floor was up. He is buried in the parish church. He was at least seventy years old, but there is no trace of senility in his Bodleian drawings. They are vigorous in design as well as drawing. The work then passed to Gerbier’s pupil, "the learned and ingenious Captain Wynne" (aka William Winde), who made several alterations to the original plan, as recorded by Horace Walpole. The credit for the majority of the house may therefore fairly be placed on his account. The character of the new work, as shown by Kip, accords with the treatment usually adopted by fellow architect, John Webb. That is to say, the walls are fairly plain, there is a wide cornice at the eaves. The height of the roof is proportioned to the walls (not merely determined by the span of the building), it is crowned by cupolas and broken by dormers and the chimneys are short and solid - perhaps, in this case, in consequence of the teaching of Gerbier, Wynne's master. It is evident that the Restoration of Charles II gave a great impetus to building. Charles himself revived the project for a new palace at Whitehall. He built a large wing of another at Greenwich. Lord Craven was among those who endeavoured to redeem the age; and Gerbier thought the occasion opportune to publish his "Counsel " to those who were contemplating new houses.

The great palace is supposed to have taken thirty-four years to complete! King William III tried to visit on his way to claim the English Throne, but the loyal Earl was in London with the monarch's rival, King James II. The next Lord Craven preferred their Warwickshire estates, but his son, William Craven III, seems to have been fond of Hamstead. Unfortunately, it was during his time that the whole place burnt to the ground in 1718. He dreamt of rebuilding and engaged James Gibbs to undertaken the work. However, when he died in 1739, little progress had been made. His brother, Fulwar, liked to hunt from the adjoining

Lodge

which was eventually converted into a smaller mansion. His heirs also built a new home at

Benham Park.

Partly edited

from

J. Alfred Gotch's 'The English Home from Charles I to George IV'

(1918).

Hamstead Marshall Park no

longer stands. However, several of its elaborate

gate piers survive. The most easily accessible are those viewed from

the churchyard.

Check out our

Hamstead Marshall T-Shirts: Forecourt

Screen & Aerial View and the

Gates that never were.

|

|