|

|

|||

|

|

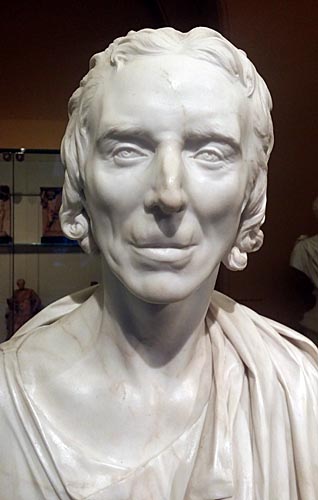

Anthony Addington, the father of the 1st Viscount Sidmouth, was born on 13th December 1718. He was the youngest son of a Berkshire gentleman, the owner and occupier of a moderately sized estate at Twyford in that county, where the family had been settled for generations. He was sent, as a commoner, to Winchester School and was elected thence to Trinity College, Oxford. He took his BA degree in 1789, that of MA in 1740 and, having fixed on medicine as his profession, he graduated MB of Oxford in 1741 and MD in 1744. About this last date, he settled as a physician at Reading, marrying, in 1745, Mary, the daughter of the Rev. Dr. Haviland John Hiley, the headmaster of the grammar school there. He obtained a good general practice and a special reputation for the treatment of mental disease. He built a house contiguous to his own for the reception of his insane patients. In 1752, Addington's testimony helped convict the infamous Mary Blandy of the murder of her father, one of his patients. The following year, Addington published, with a dedication to the Lords of the Admiralty, 'An Essay on the Sea Scurvy, wherein is proposed an Easy Method of curing that distemper at Sea, and of preserving Water Sweet for any Cruise or Voyage.' The essay displayed considerable reading, but was even then of little practical value. The method proposed for preserving the freshness of water at sea was the addition to it of muriatic acid, the hydrochloric acid of more recent chemistry. In 1754, Addington left Reading for London. In 1755, he was a candidate of the College of Physicians, in 1756 a Fellow and, being Censor in 1757, delivered the Gulstonian Lecture. For twenty years, Addington practised in London with eminent success. Among his patients was Lord Chatham, his professional connection with whom ripened into something like confidential friendship. In the 'Chatham Correspondence,' there are several letters from the statesman indicating a warm personal interest in the physician and his family. During his severe illness in 1767, Chatham respectfully declined King George III's suggestion that another physician should be called in to assist Dr. Addington. The opposition saw, in this confidence, a proof that Chatham's disease could only be insanity. This gossip, with injurious reflections on Addington's professional character, is reproduced in one of Horace Walpole's letters to Mann (5th April 1767), in which Addington is referred to as "originally a mad doctor" and as "a kind of empiric". Chatham, in a grateful letter to Addington, ascribed his recovery to his physician's "judicious sagacity and kind care." Four years before, Addington had restored to health, Chatham's second son, William Pitt the Younger, by a course of treatment that included the seductive remedy of port wine. Chatham seems to have sometimes used Addington as his mouthpiece in society and in communicating to him a striking memorandum of his views on the future of the struggle with the American colonists in the July of 1776. Chatham insisted strictly that, when repeating them in conversation with others, Addington employ "the very words" of the written paper. The Doctor's excessive zeal was perhaps concerned in the misunderstanding between Chatham and Bute in the Winter of 1778. Sir James Wright, a friend of Lord Bute, told Addington, who was his physician, that Bute desired to see Chatham recalled to office. Addington communicated this statement to Chatham, with the doubtful addition that Bute desired a coalition ministry, of which Chatham should be the head and he himself a member. Chatham was indignant about the project, which Bute disclaimed. But some months after Chatham's death in the same year, a report was diffused - originating, according to Horace Walpole, from Bute - that the overtures had been made in reverse, by Chatham to Bute. To rebut this insinuation, a statement was drawn up and issued, probably by Lady Chatham and William Pitt, certainly not by Addington, to whom its authorship has also been ascribed though both external and internal evidence proves the contrary. It was entitled 'An Authentic Account of the Part taken by the late Earl of Chatham in a Transaction which passed in the Beginning of the Year 1778.' It consisted of letters from and to Addington, Sir James Wright and Chatham, and of "Dr. Addington's narrative of the transaction." The statement and the controversial correspondence to which it gave rise were reprinted in the 'Annual Register' for 1778 and what is essential in them is to be found in the appendix to Thackeray's 'Chatham'. In 1780, Addington retired with savings sufficient for the purchase of the valuable reversionary estate of Upottery in Devon. His last years were passed in Reading, where he attended the poor gratuitously. He was called in, by the Prince of Wales, to attend George III in 1788 and was examined before parliamentary committees in regard to the King's condition. He alone foretold the early recovery which actually took place, on the ground that he had never known a case of insanity, not preceded by melancholy, which was not cured within twelve months. During his last illness, Addington was gratified by the news that his eldest son, the new Speaker, had been voted a salary of £6,000 a year, in place of the previous plan of remuneration by fees and sinecures. He remarked to a younger son, "This is but the beginning of that boy's career." He was buried in the church at Fringford, by the side of his wife, whom he lost in 1778. Edited from Leslie Stephen's 'Dictionary of National Biography' (1885).

|

|||

| © Nash Ford Publishing 2004. All Rights Reserved. | ||||

Dr. Anthony Addington

Dr. Anthony Addington