RBH Home

Maps & Travels

Articles

Legends

Towns & Villages

Castles & Houses

Churches

Biographies

Gentry

Family History

Odds & Ends

Mail David

Beware the Ghostly Hunt

Folklore or Fact?

That Herne’s ghostly figure rides around the Windsor area of a night there seems to be little doubt. He has been seen by many local inhabitants both in and out of the saddle, as far apart as Twyford (Berks) and Huntercombe (Bucks). It is not surprising that his ghost should wander over such a wide area, since Windsor Forest once spread over most of Berkshire as well as much of South Buckinghamshire and North Hampshire. It merely adds substance to the legend. There used to stand a great elm tree in Binfield, which was said to mark the centre of the Forest, so you can imagine how big it must have been. Windsor people will even tell you that at dawn and dusk you can hear the deer in the Park calling Herne’s name; and with a little imagination, you can.

There are some twenty plus recorded sightings of Herne’s hunt around Windsor, including one by Henry VIII. Often only the baying of his hounds and the sound of his horn are heard within the Great Park, though sometimes an onlooker has seen him ride by with flashing antlers upon his head. The Earl of Surrey was even able to describe his deerskin tunic, the phosphoric chain and horned owl. The lads from Eton College have been the witnesses to Herne’s appearances on several occasions. One evening in 1962 a group of them apparently found an old hunting horn in the park. Wondering how it would sound, one of the party blew it. They were all terrified at the result as Herne and his men came riding towards them through the trees. They quickly fled. More recently (1976), a guardsman on duty at the Castle claimed that a statue in the Italian garden grew horns and came to life. He would appear to have had no prior knowledge of the Herne legends.

Herne’s lone wanderings under his oak tree do not seem to have been recorded as often as one might have thought. It is said he appeared on the eve of Henry IV’s death (1413), and several times during the reign of Henry VIII (1509-1547), when the bluff king imposed his will at the expense of those around him. Then again Herne walked before Charles I’s execution (1649), or was it his capture (1646)? In more modern times, he was seen just before the two World Wars (1914 & 1939), at the outset of the Great Depression (1931), and before Edward VIII’s abdication (1936) and George VI’s death (1952).

Like any legend, there are, of course, alternative versions, though in Herne’s case, these are little known. Herne may have been bewitched by a nun, whom he carried off to a cave, deep in Windsor Forest. In a jealous rage, he killed her and, full of remorse, hung himself on the Herne’s Oak; or was it the fact that the King had defiled Herne’s unfortunate daughter that made him commit suicide? One story places him, not in Windsor Forest at all, but in Feckenham Forest near Redditch (Worcs). Here he killed a sacred stag belonging to the Abbess of Bordesley Abbey (Worcs). In consequence, he was compelled to ride the night sky with his hunt.

There has been some attempt to identify Herne

with a real life Richard Horne, a yeoman who was charged with poaching

during Henry VIII’s reign (c.1525). In various versions of the tale,

Herne has been placed in the reigns of Richard II, Henry VII, Henry VIII

and Elizabeth I. So the identification is, at least, plausible. However,

the connection between Herne and Horne is generally made from the first

ever documentation of Herne’s story, in Shakespeare’s “Merry Wives

of Windsor”. Although written in c.1597, the version we see at the

theatre today is usually enacted from a copy dated 1623. An earlier pirate

edition of 1602 exists, however, which refers, not to Herne, but to “Horne”.

Hence, some see them as one and the same. It is possible that “Horne”

was a copyist’s error, but more likely that the pirate version is an

adaptation for use anywhere outside Windsor. All local references have

therefore been changed, including the ghost of Herne, who would be unknown

everywhere but in Berkshire. Horne was therefore substituted, and his own

story may have, subsequently, become confused with Herne’s. Hence the

dismissal for poaching enters his story.

There has been some attempt to identify Herne

with a real life Richard Horne, a yeoman who was charged with poaching

during Henry VIII’s reign (c.1525). In various versions of the tale,

Herne has been placed in the reigns of Richard II, Henry VII, Henry VIII

and Elizabeth I. So the identification is, at least, plausible. However,

the connection between Herne and Horne is generally made from the first

ever documentation of Herne’s story, in Shakespeare’s “Merry Wives

of Windsor”. Although written in c.1597, the version we see at the

theatre today is usually enacted from a copy dated 1623. An earlier pirate

edition of 1602 exists, however, which refers, not to Herne, but to “Horne”.

Hence, some see them as one and the same. It is possible that “Horne”

was a copyist’s error, but more likely that the pirate version is an

adaptation for use anywhere outside Windsor. All local references have

therefore been changed, including the ghost of Herne, who would be unknown

everywhere but in Berkshire. Horne was therefore substituted, and his own

story may have, subsequently, become confused with Herne’s. Hence the

dismissal for poaching enters his story.

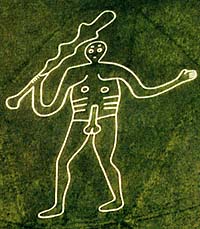

The general consensus of opinion seems to be that Herne is a distant folk memory of the ancient horned god, Cernunnos (pronounced Kurn-un-os). Cernunnos was the Celtic god of hunting and the countryside, also associated with fertility and the underworld. He was worshipped throughout Britain and Northern Europe, and his special symbols would appear to have been the oak tree and the stag. His name is known from a Gallo-Roman altar found on the site of Notre Dame in Paris. “Cerne” means horned, as in “Corn-wall” - the horn-shaped piece of land belonging to the Welsh (Celts). “Unnos” means one. So we have the “Horned One”. The Paris altar depicts him as a bearded man with human ears as well as antlers adorned with a pair of torcs. The similarities to Herne are obvious. Another portrayal of Cernunnos with additional Herne attributes can be seen on the famous Gundestrup Bowl: a silver Celtic bowl found in a peat bog near Gundestrup in Denmark in 1891. He sits cross-legged (as often depicted) with antlers sprouting from his scalp. In one hand he holds a torc, and in the other, his constant companion, a ram-headed snake (looking very much like Herne’s chain). He is attended by a large stag. There are also depictions of Cernunnos from Britain: notably a coin from Petersfield (Hants), an altar from Cirencester (Glos) and a fine mosaic from St. Albans (Herts).

The name is, however, the instantly recognisable link between Herne and Cernunnos. “Cerne” is, of course, very close to Herne. The two initial letters are analogous in Indo-European languages, and pronounced in Celtic, or even with a broad Berkshire accent, the two names sound extremely alike. There are further links between the name “Cerne” and Berkshire, for the parish of Charney Bassett, in the north of the county, derives from “Cerne-ieg”, that is the island (Saxon - Ieg) in the River Cerne. The river is, again, the Celtic “Horn”, but as this bears little relation to a river, it may stem from the god, Cernunnos. Similarly, the Iron Age hillfort of Walbury Camp (Welshman’s (ie Celt’s) Fort) was called Cornhill by Gough, and may, therefore, have been the hill of Cernunnos. Was he worshipped right across the county from Faringdon to Sunninghill?

Similarly, in Dorset, of course, there is Cerne Abbas, where the great hill-figure, the Cerne Abbas Giant dominates the surrounding countryside. There is reason to think he dates from Celtic times or even earlier (See “Royal St. George in Royal Berkshire”), so could the name imply his identity? The Welsh book of myth, the “Mabinogion” describes Cernunnos as wielding a large iron club, as does the giant at Cerne; and it is shaped like an oak leaf. However, the giant is missing the all important antlers. Could they be hidden beneath the grass? Recent surveys have revealed a similarly lost cloak slung over his left arm. This shows the giant to be Heracles, as backed up by his medieval name, Helith. However, the identification of such a Roman god with a Celtic equal, like Cernunnos perhaps, was commonplace in Roman Britain. If these two gods were seen as one and the same, he could easily be both.

It certainly seems probable that long ago, in

the days before the Romans came to these shores, there was, at the least,

a temple or sacred grove in Windsor Forest at which Cernunnos was

worshipped. It has been suggested that such a temple may have existed on

the site of the Round Tower at Windsor

Castle, or possibly where churches

now stand, in the area, dedicated to St. Nicholas, who may be a

christianised version of Old Nick, the horned-one. More feasible, however,

is the possibility that St. Leonard’s Hill (Clewer) was the centre of the

Cernunnos cult. Celtic and Roman temples were often sited on hills such as

this. Later, when Christianity came to our shores, they were converted

into Christian churches in order for the take-over to run more smoothly.

The hill in Clewer was named after St. Leonard’s Chapel: a small oratory

tended by a hermit in medieval times. Legend says it dated back to early

post-Roman times, and research has shown that dedications to St. Leonard

are often related to Cernunnos. The two had many similar attributes,

particularly the woodland settings for their shrines. Another idea has it

that a sacred grove dedicated to Cernunnos may have stood on Maidenhead

Thicket, once part of the Forest. A banked enclosure, now known as Robin

Hood’s Arbour, was excavated there earlier this century. The results

were inconclusive and it was tentatively suggested that it might have been

a pre-Roman farmstead. However, it does bear similarities to German sacred

groves called “Viereckschanzen”; and local historian Michael Bailey

suggests the arbour’s name may derive from the Celtic “Rhi-ben-hydd”

meaning “(the Place of) the King with the Deer’s Head”!

It certainly seems probable that long ago, in

the days before the Romans came to these shores, there was, at the least,

a temple or sacred grove in Windsor Forest at which Cernunnos was

worshipped. It has been suggested that such a temple may have existed on

the site of the Round Tower at Windsor

Castle, or possibly where churches

now stand, in the area, dedicated to St. Nicholas, who may be a

christianised version of Old Nick, the horned-one. More feasible, however,

is the possibility that St. Leonard’s Hill (Clewer) was the centre of the

Cernunnos cult. Celtic and Roman temples were often sited on hills such as

this. Later, when Christianity came to our shores, they were converted

into Christian churches in order for the take-over to run more smoothly.

The hill in Clewer was named after St. Leonard’s Chapel: a small oratory

tended by a hermit in medieval times. Legend says it dated back to early

post-Roman times, and research has shown that dedications to St. Leonard

are often related to Cernunnos. The two had many similar attributes,

particularly the woodland settings for their shrines. Another idea has it

that a sacred grove dedicated to Cernunnos may have stood on Maidenhead

Thicket, once part of the Forest. A banked enclosure, now known as Robin

Hood’s Arbour, was excavated there earlier this century. The results

were inconclusive and it was tentatively suggested that it might have been

a pre-Roman farmstead. However, it does bear similarities to German sacred

groves called “Viereckschanzen”; and local historian Michael Bailey

suggests the arbour’s name may derive from the Celtic “Rhi-ben-hydd”

meaning “(the Place of) the King with the Deer’s Head”!

If this is so, could it be that Cernunnos’ priests wore antlers just like their god: Herne being a folk memory of these men passed down the generations? The Shamans of Northern Asia certainly dressed this way, and there is evidence that similar apparel was once worn in prehistoric rituals in Britain. The hunter-gatherer site excavated at Star Carr near Pickering (Yorks) exposed parts of some 102 sets of deer antlers. Many contained thong holes to enable attachment to one’s head! Dressing up as animals, especially deer and horses, at christianised religious festivals took place in various parts of Europe right up to the Middle Ages. Several influential churchmen, including St. Augustine, are recorded, naturally enough, to have condemned such practices.

Shamans, like Herne, are also associated with trees. They placed them at the centre of the village to be used as a way of ascending to heaven. The oak tree feature of the Herne legend is the major link with a second deity, additional to Cernunnos. Woden (Odin in Norse mythology), chief of the Saxon gods also once hanged himself from a tree: in his case, an ash tree. He was pierced with a spear, and hoped that, by staying there nine days and nights, he would learn the secrets of the runic alphabet. In fact, in the parish of Chieveley, there once stood a tree known as the “Woden Tree”. Notable Trees, named after or associated with famous personages, are not uncommon in Britain. The most well known are, perhaps, the Major Oak in Sherwood Forest (Notts) where Robin Hood and his merry men used to meet, and the Boscobel Oak (Salop) where Charles II hid from the Parliamentarians. In Berkshire, the Binfield Elm has already been noted. There was also, once, Nan’s Oak in White Waltham, the largest oak in the country, under which Queen Anne Hyde (a lady, supposedly, from an old Berkshire family) was said to have rested and become mortally ill. In the Great Park another famous oak was the lost King’s Oak. In Nearby Burnham Beeches (Bucks) there still stands Druid’s Oak, reminding us that this tree, as well as the white hart, was once sacred to the men of the old pagan religion. Was Urwick one of these men? It is possible that Berkshire was a particularly special area in the worship of the oak tree and related gods. Its name may derive from the Saxon “Bearu-Ac-Scire”, that is the “Oak Grove Shire”. Certainly, Herne’s Oak and the deer he chased (or possibly the man himself in such a guise) are still inseparably linked with the county. They appear as the crest of the county arms. Many organisations use the duo as their badge and even show the oak as but half a tree, having been split by lightning in the presence of King Richard.

Woden later became leader of the “Wild Hunt” of lost souls, which rode furiously across the sky on stormy nights. It was said to foretell great misfortune. This Wild Hunt theme is found all over Europe, as well as in Britain. Being at the head of the hunt, Woden was known as “Herian”: the leader of the host. The name may be related to King Herla who leads the hunt in Herefordshire; to Harlequin who takes his place in France; to Helith, the giant of Cerne Abbas (discussed above); and, of course, to Herne himself. Elsewhere in Berkshire, around Littlewick Green, the hunt is led by the ghost of Dorcas Noble. This young girl was forced to ride the night’s sky after being beheaded for using witchcraft to defeat a rival in love. In Welsh Celtic myth, it was the underworld god, Arawn, who rode with the hunt, chasing, like Herne, a white hart. In Devon, the Devil, or perhaps the Saxon war god, Tiw, leads the chase across Dartmoor. With his “Wisht Hounds”, he searches for the souls of unbaptised children and people who became lost on the moor. The hunt begins at the Dewerstone (Tiw’s Stone) Rock near Bickleigh.

The “Horned One” in the Christian world is, of course, personified by the Devil. So the hunts of Devon and Berkshire may well be headed by the same character. To those who believe in the supernatural there is certain proof. One night, in February 1855, a series of, what appeared to be, hoofprints were discovered in the snow all across South Devon. They stretched over one hundred miles, from Teignmouth to Exmouth, at one point jumping the two mile wide Exe Estuary. The prints went up walls and over roofs, and their appearance soon became known as “The Great Devon Mystery”. However, the locals all knew from whence the prints came: They were the work of the Devil and his Wild Hunt. To return to Windsor, a man living in Burnham (Bucks) once heard Herne and his followers thundering through the night’s sky above his house. In the morning he discovered hoofprints impressed right over his roof!