|

|

|||

|

|

Medieval St.

Laurence's Church, Reading Medieval St.

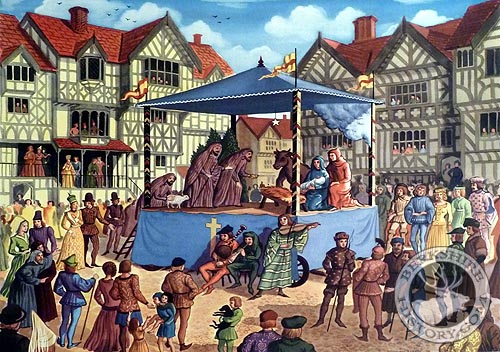

Laurence's Church, ReadingA Walk through a Different Age Hard by the Compter Gate to Reading Abbey stood the church of St. Laurence. The church formed part of the Abbey boundary, and if you have seen how the church of St. Margaret, at Westminster, seems to nestle beneath the shadow of the towering Abbey by its side, you will have some notion how the church of St. Laurence used to look before the Abbey of Reading was destroyed. Between 1400 and 1540 the parishioners of St. Laurence did all they could to improve their church and to make it beautiful. They rebuilt much of it. In 1458, the tower took the form it still has today and, about this time, the number of bells was increased from three to five. ‘Harry,’ the biggest bell, weighed thirty-six hundredweight and was given by, and named after, a rich clothier, Henry Kelsall (1494). New organs, new windows, new seats, a new font, a new roof and a new clock were also provided. The old clock of 1499 was a curious one. It had a Jack, or figure of a man, which sounded the hours by striking a bell with a hammer. Much gilding and painting was done, and the churchyard was enlarged. The cost of these works was borne by the people of the parish. Lists of their gifts, many of them the small gifts of poor people, still remain. The larger gifts usually came from the wealthier clothiers. English churches have changed so much in appearance and in the purposes which they serve, since those days, that it is not easy to recall what this fine old church of St. Laurence was then like, and what it meant in the life of the people. The walls within were rich with paintings and tapestries depicting scenes from the Bible and the story of Christianity. The columns and arches which supported the roof were brightly coloured, and the timbers of the roof shone with paint and gold. As many as twelve altars stood about the church in honour of different saints. One of these was the altar of St. Blaise, patron saint of wool merchants, then so numerous in Reading. Another was the altar of St. Clement, patron saint of smiths: his pincers, hatchet and sword were represented. Then there was an image of St. George, patron saint of England, armed with sword and dagger, and bestriding a steed coated with horse-skin. Upon the floor of the church gleamed figured and lettered brasses in memory of the dead. In all parts of the church the brightness of colour and of gold caught the eye. The windows were of painted glass, and the church was divided into two parts by a carved screen and the rood loft. In the vestry was kept, securely in chests, a rich treasure of silver plate, books, banners and vestments. The people of those days delighted in shows and pageantry and, in their opinion, the parish church was the place for these things. Perhaps we should remember that there were then no theatres, concerts, lectures, clubs or libraries. It was to the church that men went, not only to worship and to be serious, but to make merry and to rejoice in splendid pageants. There was hardly a week in the year without its feast or ceremony in the parish church. These bygone ceremonies and customs cannot all be described, but a little may be said about a few of them. Easter Monday and Easter Tuesday were called ‘Hock Tide’. In a ceremony not dissimilar to that still celebrated at Hungerford today, men went through the streets carrying a rope, with which they entangled anyone who met them on the Monday. These captives were not released until they had paid the men a ‘fine’. On the Tuesday, women took the rope, and they, of course, always managed to gain more money than the men. The profits from Hock Tide were donated to the church. Soon after Easter, came May Day, when great feastings were held. It was the custom to perform a play. One of these plays was called the May Play (or Robin Hood) and another was called the King Play. The first was a representation of the story of Robin Hood, Maid Marian, Friar Tuck and Little John. The second was an acting of the story of the Wise Men from the East, the three kings who, according to an old legend, were said to have been eventually buried at Cologne. The May Day merrymakings began early. At daybreak ‘young folks and maidens,’ some carrying banners, went forth to the woods to cut down a ‘summer pole.’ This pole they brought home in triumph, and set it up in the Market Place, or at the door of the church. Stands were erected at the church porch for the older spectators, who wore ribands and badges. Minstrels played harps and other instruments, and morris dancers, in coats of painted buckram hung with jingling bells, danced to the merry music. Then came the plays. Later in the day a feast was held in the church. On Corpus Christi Day - the Thursday after Trinity Sunday - the bells rang a peal and a procession with banners went about the streets. A third play was then performed. On this occasion, a stage was erected in the Forbury and decked with green boughs. Among the characters in the play were usually Adam and Eve. The lights for this play were provided by the tailors and shoemakers of the parish. Sometimes, as at Whitsuntide, gatherings called church ales were held. The church was well cleaned, plenty of pasties and other food was prepared, a musician was hired and then the parishioners assembled inside the church and feasted together. Profits arising from these gatherings were handed to the churchwardens. Many old ceremonies and customs were then observed which have since been abolished or forgotten. For instance, the bells of the church had godfathers and godmothers. These customs had grown up in the course of ages and, though some of them may now seem superstitious and wrong, the people of those days liked them and put faith in them. Prosperous parishioners gave freely of their wealth in order to add to the splendour of the church and its services, or to its furniture. For example, one gave to the church a model ship of silver and two silver candlesticks. Another gave money for a bell. Another gave two service books with covers of carved and gilded silver. A builder gave the church a ladder. Few churches in England were richer in treasure. It was in this way that the church encouraged skilled handicrafts. The churches of Reading employed builders, bell-founders, tapestry weavers, embroiderers, mural painters, carvers in wood, stone and metal, and painters on glass. The carving in St. Laurence's Church was the work of a Reading carver. The stained glass, once in the chancel, was the work of a Reading man. The wall painting of St. Christopher, opposite the entrance, and the gilding in the church, and many other beautiful things were executed by Reading craftsmen. The bells made at Reading were noted throughout this part of England. In Berkshire, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire, and even in districts more remote, the bells of churches were often procured from the foundries at Reading. Edited from W.M. Childs' "The Story of the Town of Reading" (1905)

|

|||

| © Nash Ford Publishing 2017. All Rights Reserved. | ||||