|

|

|

Reading Four Reading Four

Hundred Years Ago

A Wealthy Merchant Town

in Tudor Times

Let us try to picture to

ourselves, Reading as it

was about the end of Queen Elizabeth I's long reign (1558-1603) and the

beginning of the Stuart period. The cloth trade was then at the height

of its prosperity. It is not likely, however, that, in 1600, Reading

contained more than about 5,000 people. Most of them dwelt within the

space marked out by Old Street (now St. Mary's Butts and West Street),

Friar Street, the Market Place and the Hallowed Brook. There were,

however, a good many houses in Castle Street and in London Street. In

1610, there were no regular places of worship other than the three old

parish churches. Though it is possible that, as early as this date, a

few people may have been in the habit of meeting together privately to

worship God in their own way, since it is known that, more than a

century before 1610, there were a few Lollards (followers of John

Wycliffe) in Reading.

Much traffic, consisting chiefly of pack-horses and wagons, passed

through the town along the western road from Bristol to London, and also

along the road which led over Caversham

Bridge to Oxford. Many barges passed to and from Reading by the Kennet

and the Thames. Reading, in fact, had now become the chief town in

Berkshire and many observers praised the handsomeness of its streets and

houses.

It was a town of many bridges. In the year 1560, there were certainly

nineteen. Seven of them were in the short street which crossed the

streams of the Kennet. This street, now called Bridge Street, was then

called Seven Bridges. Further, there were six bridges between Caversham

Bridge and the remains of the Friary. Several of the brooks which these

bridges crossed have since disappeared. Caversham Bridge itself was very

ancient and curious. Part of it was wood and part was stone. Half-way

across it were the remains of the old chapel of St. Anne, in earlier

days visited by numberless pilgrims because of its celebrated relics.

All round the town, and quite close even to the main streets, there were

green fields and, within the town, there were many gardens and orchards.

The streets were, however, very narrow and crooked. Many of them were

called "rows." The houses were so built that each storey

overhung the one below it and, though their timbered fronts and numerous

gables were pleasing to behold, the effect of building thus was to shut

out light from the windows and road below. Moreover, many houses bore

swinging signs, hung out over the roadway on poles, and these signs made

things darker still. The pavement of the streets was very uneven. At

best, it consisted of flints and round pebbles rammed tightly together.

A gutter ran down the middle of the street and all kinds of refuse

collected in it. There was only one regular scavenger and his work was

to cleanse part of the town once a week. The pigs which strayed about

the streets, and the surly dogs which lurked in doorways, perhaps made

up a little for the lack of proper scavengers. There was no general

system of drainage whatever at this time. Water, never filtered, was

obtained from the rivers or out of wells. The lighting of the streets,

at night, was then and long afterwards very poor. It was thought enough

for householders to hang a lantern outside their doors on nights when

there was no moon. There were no fire engines. A few leather buckets and

some ladders were the only appliances in case of a house catching fire.

Fear of fire caused the Corporation to forbid any one to use thatch for

roofing. At nine o'clock at night, the deep voice of "Harry,"

the big bell in St.

Lawrence's tower, warned the people to go to bed and, at five

o'clock in the morning, it warned them to get up.

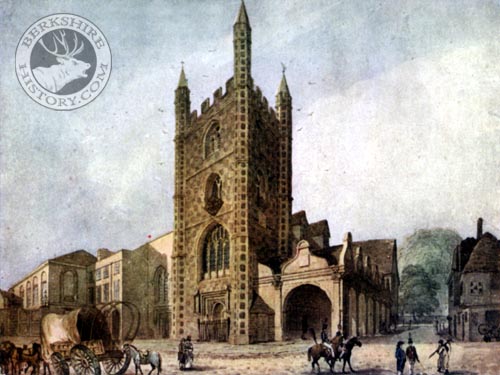

It was more than sixty years since the monks had been turned out of the Abbey,

and large parts of their ancient habitation had been pulled down. But it

would seem that the tower and spire of the great church yet stood and so

also did the noble chapter house. Enough of the old house of the Grey

Friars remained in 1614 to make it a suitable lodging for Queen Anne,

the wife of James I. The house was then approached from the street

through an imposing arched gateway. The guest hall of St.

John's Hospital was used for a town hall and for a free school,

while the old dormitory of the Hospital had been turned into stables for

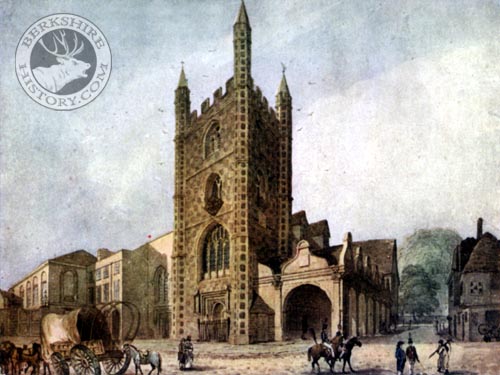

the King's horses. In 1611, John

Blagrave, the mathematician, left some money to make the Market

Place larger and also to build, against the side of St. Lawrence's

church, facing the Market Place, a covered walk, or cloister, for the

shelter and comfort of market women and others. In some of the old

pictures of the church this cloister may be observed. In the middle of

the Market Place were the town pump, the whipping posts, the pillory and

the stocks.

It was more than sixty years since the monks had been turned out of the Abbey,

and large parts of their ancient habitation had been pulled down. But it

would seem that the tower and spire of the great church yet stood and so

also did the noble chapter house. Enough of the old house of the Grey

Friars remained in 1614 to make it a suitable lodging for Queen Anne,

the wife of James I. The house was then approached from the street

through an imposing arched gateway. The guest hall of St.

John's Hospital was used for a town hall and for a free school,

while the old dormitory of the Hospital had been turned into stables for

the King's horses. In 1611, John

Blagrave, the mathematician, left some money to make the Market

Place larger and also to build, against the side of St. Lawrence's

church, facing the Market Place, a covered walk, or cloister, for the

shelter and comfort of market women and others. In some of the old

pictures of the church this cloister may be observed. In the middle of

the Market Place were the town pump, the whipping posts, the pillory and

the stocks.

If we study the map of Reading

in 1610, and also other sources of information, we notice many

differences in the names and arrangement of the streets. Here are a few

examples. The street now called Cross Street was then called Gutter

Lane. The east end of Broad Street was split into Butchers' Row and Fish

Street, and a cluster of houses stood in the middle of the Butts. Near

Butchers' Row were the wool hall and the cloth market.

Between West Street and the old post office were the sheep market and

the pig market. The corner by the Friary was called the Town End.

Minster Street was so narrow, and so often blocked with wagons, that, in

1648, the Corporation closed it with chains: hence nearby Chain Street.

There were archery butts in St. Mary's parish and in St. Giles's parish.

On Whitley Hill, there were some wooden houses, occasionally used for

the reception of those stricken with the plague. There was no proper

hospital for the sick or injured.

There were many inns in the town. The chief of these were the George Inn

and the Bear Inn. The George was already old, for it is said that it was

built in 1506. It still continues, but the Bear has been closed many

years past. The Ship, the White Hart and the Broad Face also existed in

the seventeenth century, but only the first remains today.

On market days, the Market Place was thronged with countryfolk,

especially towards noon. If you could visit it at such times, you would

be likely to see many curious sights. You would see the aldermen of the

Corporation going to the Town Hall in their furred gowns and the

burgesses' sons going to the Free School. Yonder, might be an Arabian

quack doctor trying to persuade people to buy his drugs; or a ragged

footpad caught in the act of cutting a woman's purse from her girdle.

Here, the people would gather round the town sergeants about to cry, in

a loud voice, a proclamation fresh from London. Yonder, would be a group

of travelling actors, anxious to be allowed to act their play in the

Town Hall; or a knot of people who professed to have discovered a witch.

Here, would be two men fighting with cudgels and the constable running

up to stop them. Seated on the ground, with their feet fast in the

stocks, might be a drunkard or two, or a man caught swearing bad oaths.

All sorts of people, travelling on the great roads, drifted through

Reading and idled about the Market Place on market days: sailors from

the western ports, soldiers on the march, fugitives from justice,

workmen without work, Irishmen and even Dutchmen, thieves and honest

folk. The constables were very anxious to prevent beggars from stopping

in the town and we even read of one official, called the "cripple

carrier," whose duty it was to carry cripples beyond the borough

boundary.

Such then was Reading about four centuries ago. The town was on the

threshold of memorable events. Those events, especially the Civil

War, were to leave lasting marks upon its life, its well-being

and upon its appearance.

From WM

Childs' "The Story of the Town of Reading" (1905)

|

|

Reading Four

Reading Four

It was more than sixty years since the monks had been turned out of the

It was more than sixty years since the monks had been turned out of the