|

|

|||

|

|

Reading Prisons

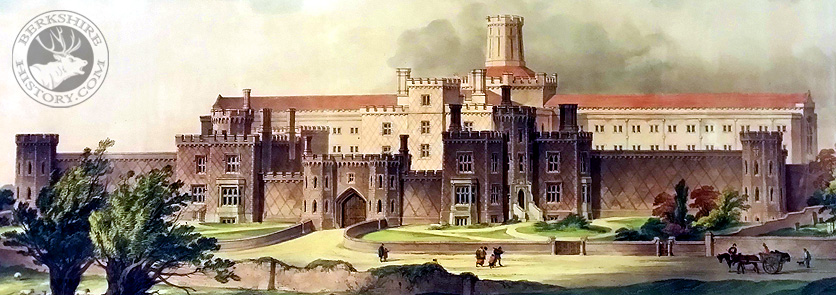

& Punishment Until about the middle of the 19th century, any kind of building was thought good enough for a prison, and no punishment was too severe to inflict on those who had broken the law. John Howard, the famous prison reformer, visited the Reading prisons four times between 1773 and 1779. At that time, the county gaol stood at the foot of Castle Street, and it was in a very bad condition. In 1793, the gaol was rebuilt in the Forbury and made large enough to hold 124 prisoners. The Reading Gaol was one of the first to introduce the tread-mill as a form of punishment, and it became the custom for people to go and watch prisoners undergoing their painful and useless labour of treading the mill. This gaol was in its turn condemned, and a new gaol was opened in the year 1844. John Howard also visited the town prison, which at that time was the old church of the Greyfriars. He found it filthy and ruinous, without any court for exercise, and without water. There was no means of warming it, there was no proper drainage, and the place was overrun by rats. One of the cells was also used as a stable. There was no infirmary or sick-room, and there was no religious instruction or care given to the prisoners. Yet, in 1829, the Mayor of Reading said the prison was good enough for its purpose. Public opinion, however, now insisted on a change and soon afterwards this prison was closed. Around the turn of the 19th century, there were no policemen in Reading. One or two watchmen with lanterns used to pace the streets at night, calling out the hour and what the weather was. The watchmen were so few that they were quite unable to keep the town in good order. Robberies and begging, street-fighting and other disorders were frequent. It was largely because there were no police, and because messages travelled along the roads so slowly, that highway robberies were so common. A highwayman upon a fast horse was not easily caught. There are many instances of coaches and travellers being stopped and robbed, even within sight of Reading. In 1814, banknotes, worth £6,000, were stolen from a coach on its way from London to Reading. In 1817, a Catholic clergyman, returning from Wallingford to Reading with a sum of money in his pocket, was robbed and murdered in the Oxford Road, not far from where the present barracks stand. Punishments for such crimes were severe. Men were transported for seven years for trifling thefts, such as stealing a pair of shoes or a silk handkerchief. They were hanged, not only for wilful murder, but for stealing sheep, or for burglary, or robbery on the highway. Thus, in 1800, eight men were sentenced to death at Reading Assizes, but only one of them had committed murder. Until 1793, those who were condemned to death at Reading were hanged on Gallows Tree Common, at Lower Earley. The cart in which the prisoner rode used to stop at the Oxford Arms in Silver Street, and the hangman and his victim used to drink together. In later years, executions took place, in public, at the county gaol, and large crowds used to gather to see the death sentence carried out. The old punishments of the pillory, stocks and whipping-post were still occasionally used at the beginning of the 19th century. In 1812, for example, a Reading tradesman was seen to purchase two baskets of eggs in order to pelt a man who had been put in the pillory in the Market Place. Thieves and beggars were flogged in the Market Place as late as 1819. About the same date, a wretched man, whose only offence was that he had stolen a loaf, was flogged at the cart's tail from the prison in Friar Street to his house in Silver Street. Such was the brutality of his punishment that he never recovered or left his house again. In 1830 and 1831, Reading Gaol was crowded with country labourers, accused of burning the farmers' stacks of corn in revenge for the introduction of steam threshing machines. The men feared that these machines would cause less labour to be wanted. Night after night, Reading people used to see, from the Forbury, the red glare of fires in the villages around. A guard of soldiers was sent from Windsor to protect the town. When the prisoners, 138 in number, were brought to trial, it was found that 76 of them could neither read nor write. Many of them were imprisoned; some were transported ; three were condemned to death. Through the efforts of two members of the Society of Friends in Reading, two of these three were reprieved. The third was hanged at Reading. Partly edited from W.M. Childs' "The Story of the Town of Reading" (1905)

|

|||

| © Nash Ford Publishing 2017. All Rights Reserved. | ||||